Mary Jenkins, Sally Jenkins, and Lyle Jenkins obtained a special permit from the Town of Marshfield Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) to allow the construction of a barn on a vacant lot that lacks sufficient depth under the Marshfield Zoning Bylaw (Bylaw). The plaintiffs, most of whom abut the lot, challenge the special permit. The parties have brought cross-motions for summary judgment. The plaintiffs presumption of standing has not been rebutted, and the merits of their appeal are considered. On the merits, the special permit was not properly granted because there is no lawful nonconforming structure on or nonconforming use of the lot that could be the subject of a special permit under G.L. c. 40A, § 6, and the Bylaw, and the lot does not qualify as a Residential Lot of Record under the Bylaw. The plaintiffs summary judgment motion will be allowed, the defendants cross-motion for summary judgment denied, and judgment will enter annulling the special permit.

Procedural History

Norwin Wolff, Patti Wolff, Kelly L. Newell, Edward J. Newell IV, James Reich, Ellen A. OConnor, Carlos G. Peña, and Maureen Peña (the Abutters) filed their complaint on April 18, 2014, naming as defendants members of the ZBA and private defendants Mary Jenkins, Sally Jenkins, Karen McArdle, Carl G. Emilson and David P. Emilson. The case management conference was held on May 20, 2014. On June 20, 2014, the Abutters filed a notice of dismissal for defendants Karen McArdle, Carl G. Emilson, and David P. Emilson, and moved for leave to file an Amended Complaint to add as plaintiffs James F. Reich, Ellen A. OConnor, Carlos G. Peña, and Maureen Peña, and to add Lyle Jenkins as a defendant. On July 8, 2014, a hearing on the Abutters motion to amend their complaint was held and the motion allowed, and the Abutters first amended complaint was docketed. The Abutters filed the Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment (Plaintiffs Summary Judgment Motion), Memorandum of Law in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment, and Plaintiffs Statement of Undisputed Facts with Exhibits in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment on March 16, 2015. The Jenkins Family filed Private Defendants Cross Motion for Summary Judgment (Defendants Summary Judgment Motion) and a Memorandum in Support of Defendants Cross Motion for Summary Judgment and Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment with a Table of Authorities and Exhibits on April 3, 2015. The Abutters filed Plaintiffs Opposition to Private Defendants Motion for Summary Judgment on May 1, 2015. The Summary Judgment Motions were heard on May 21, 2015, and taken under advisement. This Memorandum and Order follows.

Summary Judgment Standard

Generally, summary judgment may be entered if the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court is to draw all logically permissible inferences from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). Summary judgment is appropriate when, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law. Regis Coll. v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Undisputed Facts

The following facts are undisputed.

1. Defendant Sally Jenkins is the co-owner of the residence at 107 Canoe Tree Way West, Marshfield, MA (Jenkins Property), shown on the Marshfield Assessors Map (Assessors Map) as Parcel 01-03. First Amended Complaint ¶ 31 (Compl.); Answer ¶ 31 (Ans.); Appendix to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment Exhibit 1, 2 (hereinafter App. Exh. _).

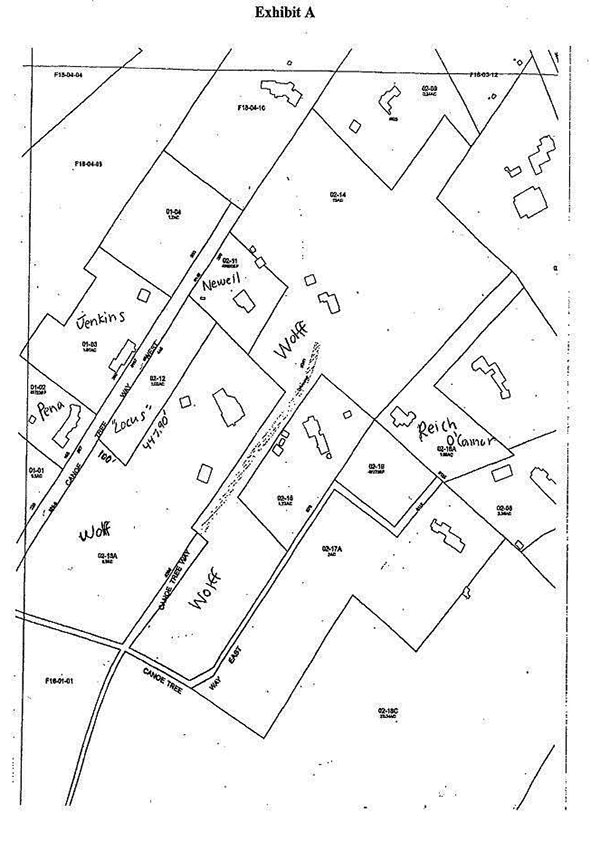

2. The Jenkins Property is approximately 1.91 acres, consisting of a single family residential structure and a garage converted into a barn that currently houses their horses. Compl. ¶ 31, Ans. ¶ 31. The location of the barn on the Jenkins Property is in the approximate location of the small square shown on the Assessors Map on Parcel 01-03. Affidavit of Patti C. Wolff in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment ¶ 27 (hereinafter Wolf Aff. ¶ _, Exh, _); Affidavit of Carlos G. Peña in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment ¶ 32 (hereinafter Peña Aff. ¶ _, Exh, _).

3. Located directly across from the Jenkins Property is the lot at 0 Canoe Tree Way which is the subject matter of this action, shown on the Assessors Map as Parcel 02- 12 (Locus). App. Exh. 2.

4. The Locus was created by deed dated May 27, 1955 and recorded with the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 2424, Page 81. App. Exh. 8.

5. The Locus is a 1.03-acre rectangular parcel 447.90 feet wide by 100 feet deep. Compl. ¶ 17; Ans. ¶ 17; App. Exh. 10.

6. The Locus is located in the Residential Rural Zoning District (R-1 district) within the Town of Marshfield under the Bylaw. Compl. ¶ 19, Ans. ¶ 19; App. Exh. 9.

7. At the time it was created, the Locus conformed with the then-existing Bylaw.

8. In 1972, the Town amended the Bylaw to change the R-1 Districts minimum lot depth to 150 feet.

9. Currently, the Locus meets all dimensional requirements for a lot in an R-1 district under the Bylaw, except for the minimum lot depth of 150 feet. Accordingly, the Locus is a nonconforming lot. Compl. ¶ 19, Ans. ¶ 19; App. Exh. 11.

10. Sally Jenkins, along with her parents Mary and Lyle Jenkins (the Jenkins Family), purchased the Locus by a deed dated May 15, 2014 and recorded in the registry in Book 44320, Page 214. Compl. ¶¶ 12-14; Ans. ¶¶ 12-14; App. Exh. 3.

11. Plaintiffs Norwin Wolff and Patti C. Wolff own the property at 209 Canoe Tree Way, Marshfield Hills, Massachusetts (Wolff Property), shown on the Assessors Map as Parcel 02-13A and 02-14. The Wolff Property directly abuts the Locus. There is a pool, cabana and tennis courts on the Wolff Property, located directly behind the proposed location of the horse barn on the Locus. Compl. ¶ 21; Ans. ¶ 21; App. Exhs. 2, 4. See Wolff Aff. ¶ 40; App. Exh. 2.

12. Plaintiffs Kelly L. Newell and Edward J. Newell IV own the property at 148 Canoe Tree Way West, Marshfield Hills, Massachusetts (Newell Property), shown on the Assessors Map as Parcel 02-11. The Newell Property directly abuts the Locus to the northeast. Compl. ¶ 25, Ans. ¶ 25; App. Exh. 5.

13. Plaintiffs Carlos G. Peña and Maureen Peña own the property at 87 Canoe Tree Way West, Marshfield Hills, Massachusetts (Peña Property), shown on the Assessors Map as Parcel 01-02. The Peña Property does not directly abut the Locus, but lies across Canoe Tree Way West within 300 feet of the Locus. Compl. ¶ 28; Ans. ¶ 28; App. Exhs. 2, 6.

14. Plaintiffs James Reich and Ellen A. OConnor own the property at 125 Canoe Tree Way East, Marshfield Hills, Massachusetts (Reich Property), shown on the Assessors Map as Parcel 02-16A. The Reich Property does not abut the Locus. Compl. ¶ 27; Ans. ¶ 27; App. Exh. 2, 7.

15. The Locus and the Jenkins, Wolff, Newell, Peña, and Reich Properties are shown on the plan attached hereto as Exhibit A.

16. On November 13, 2013, the Jenkins Family filed an application for a special permit, pursuant to section 10.12 of the Bylaw and an application for a variance pursuant to section 10.11 of the Bylaw (together, the Application). In the Application, the Jenkins Family sought to construct a 30 foot by 40 foot horse barn (barn) on the Locus. Compl. ¶ 32; Ans. ¶ 32; App. Exh. 15, 16.

17. The Jenkins Family intends to house their horses at the barn on the Locus, store feed and horse supplies, and compost manure near the barn. Mary Jenkins Answers to Interrogatories ¶ 16 (hereinafter Jenkins Interrog.); App. Exh. 18.

18. The proposed location of the barn is closer to the Wolff Property and Peña Property than the barn currently on the Jenkins Property. See Wolff Aff. ¶ 34; Peña Aff. ¶ 37.

19. Prior to the date of the Application, there was no structure on the Locus other than a utility pole and a wire fence and it served as a vacant, undeveloped wooded lot. See Wolf Aff. ¶ 9-11; Affidavit of Kelly L. Newell in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment ¶¶ 8-10 (hereinafter Newell Aff. ¶ _, Exh, _).

20. Section 10.12 of the Bylaw authorizes the grant of a special permit for extensions or alterations of nonconforming uses or nonconforming structures, and states in relevant part:

Upon written application, duly made to the Board and subsequent public hearing duly advertised by the Board, the Board may, in appropriate cases, subject to the applicable conditions set forth in Articles XI, XII, XIII, and XV of this Bylaw and elsewhere, and subject to other appropriate conditions and safeguards, grant a special permit for an extension or alteration of a nonconforming use or structure. The Board may, subject to the same conditions, grant a special permit for expansion of parking and other accessory uses appropriate to said nonconforming use or structure or expanded nonconforming use or structure.

App. Exh. 11.

21. A public hearing was held regarding the Application on December 10, 2013, and was continued to January 14, 2014 (no testimony given), January 28, 2014 (no testimony given), February 11, 2014, and March 11, 2014. Compl. ¶ 37; Ans. ¶ 37.

22. On March 25, 2014, the Marshfield Zoning Board of Appeals (the ZBA or Board) issued a decision (the Decision) denying a variance under Section 10.11 of the Bylaw and granting a special permit under Section 10.12 of the Bylaw for the use of a pre- existing nonconforming lot . . . to construct a 30 x 40 barn to house horses and store feed and to install a fence on [the Locus]. Compl. ¶ 38; Ans. ¶ 38; App. Exh. 9.

23. The ZBA found that:

(1) the use requested is listed in the Table of Use Regulations as a permitted use;

(2) the requested use is essential or desirable to the public convenience or welfare;

(3) the requested use will not further create undue traffic congestion or unduly impair pedestrian safety;

(4) the requested use will not further overload any public water, drainage, or sewer system or any other municipal system to such an extent that the requested use or any developed use in the immediate area or in any other area of Town will be unduly subjected to hazards affecting health, safety, or the general welfare;

(5) any special regulations for the use or structure as set forth in Article XII are fulfilled or not applicable;

(6) the requested use will not bring the structure into violation of, or further violation of, the regulations set forth in Article IV, Table Dimensional and Density Regulations;

(7) the use will not be more detrimental or objectionable to the neighborhood;

(8) the use does not cause violation of Article VIII of the Marshfield Zoning Bylaws.

App. Exh. 9.

24. In June 2014, after the Decision was issued, the Jenkins Family cleared the Locus of existing trees and vegetation in order to construct the barn. The Jenkins Family brought three horses into the neighborhood in late summer or early fall of 2014. See Wolff Aff. ¶¶ 14, 25. The Locus is presently being used as a pasture for three horses while the horses are currently being kept at night in the existing barn on the Jenkins Property until the new barn is built. Id. ¶¶ 26, 27.

Discussion

The Jenkins Family has moved for summary judgment on two grounds: first, that the Abutters lack standing; and, second, that the Decision should be affirmed on the merits. The Abutters argue the opposite: that based on the summary judgment record they have standing and the Decision should be annulled. The questions of standing and the merits of the Decision are discussed in turn.

Standing.

In order to have standing to challenge the issuance of the Decision upholding the Jenkins Familys special permit, the Abutters must be person[s] aggrieved by the Decision. G.L. c. 40A, § 17; Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 117 (2011); Planning Bd. of Marshfield v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Pembroke, 427 Mass. 699 , 702-703 (1998). Persons entitled to notice under G.L. c. 40A, § 11, including abutters to the subject property and abutters to abutters within 300 feet of the subject property, are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved within the meaning of § 17. G.L. c. 40A, § 11; 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Choate v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Mashpee, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 376 , 381 (2006). The record shows that the Wolff Property, Newell Property, and Peña Property abut or are abutters to abutters located within 300 feet of the Locus. Therefore, they are entitled to the presumption that they are aggrieved. See App. Exh. 2.

In the zoning context, a defendant can rebut an abutters presumption of standing at summary judgment in two ways. First, the defendant can show that, as a matter of law, the claims of aggrievement raised by an abutter, either in the complaint or during discovery, are not interests that the Zoning Act is intended to protect. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 702, citing Kenner, 459 Mass. at 120. Second, where an abutter has alleged harm to an interest protected by the zoning laws, a defendant can rebut the presumption of standing by coming forward with credible affirmative evidence that refutes the presumption. Id. at 703. [T]he defendant may present affidavits of experts establishing that an abutter's allegations of harm are unfounded or de minimis. Id., citing Kenner, 459 Mass at 119120, and Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 2324 (2006). A defendant need not present affirmative evidence that refutes a plaintiffs basis for standing; it is enough that the moving party demonstrate by reference to material described in Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c), [ 365 Mass. 824 (1974)] unmet by countervailing materials, that the party opposing the motion has no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable injury. Id., quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35; Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 716 (1991). Once the presumption of standing has been rebutted successfully, the plaintiff [has] the burden of presenting credible evidence to substantiate the allegations of aggrievement, thereby creating a genuine issue of material fact whether the plaintiff has standing and rendering summary judgment inappropriate. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 703 n.15, citing Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Sutton, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 515 , 519521 (2011).

In other words, if their presumption of standing is rebutted, the Abutters would bear the burden to present evidence that would establish that they will suffer some direct injury to a private right, private property interest, or private legal interest as a result of the Decision that is special and different from the injury the Decision will cause to the community at large, and that the injured right or interest is one that c. 40A or the Bylaw is intended to protect, either explicitly or implicitly. Id. at 700; Kenner, 459 Mass. at 120; Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 27-28; Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005); Barvenik v. Board of Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132-133 (1992); see Ginther v. Commissioner of Ins., 427 Mass. 319 , 322 (1998). Aggrievement is not defined narrowly; however, it does require a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm. Kenner, 459 Mass. at 121-123 (finding the height of the new structure to have a de minimis impact on plaintiffs ocean view). The evidence must be both quantitative and qualitative. Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441. Quantitative evidence must provide specific factual support for each injury the plaintiff claims. Id. Qualitative evidence is held to a reasonable person standard. Id.

The Abutters argue that all the harms they claim they will suffer are a direct result of the Jenkins Familys proposed barn. The Jenkins Family does not claim that these harms are not interests protected by G.L. c. 40A or the Bylaw. Rather, they attempt to rebut the Abutters presumption of standing by arguing that the claimed harms do not relate to the barn, but instead resulted from the clearing of the Locus. The Abutters claimed harms can be divided into four categories: (1) odor; (2) privacy; (3) stormwater runoff; and (4) traffic. They are examined in turn.

1. Odor

The Abutters assert that they will be harmed by increased noxious odors and accompanying pests as a result of the barn on the Locus. Currently, the Jenkins Family keeps their horses in a barn on the Jenkins Property and composts manure near that barn. See Wolff Aff. ¶¶ 26, 27. Affidavits from several Abutters clearly demonstrate that they are already subjected to offensive smells and pests, such as flies, that come from the keeping of horses, most noticeable at or near the barn on the Jenkins Property. Id. ¶ 29; Peña Aff. ¶¶ 34, 36. The location of the proposed barn approved by the ZBA is closer to the Abutters properties than the currently used barn. In particular, the new barn would be directly behind the pool, cabana, and tennis courts on the Wolff Property, which the family uses considerably during the summer months. The Jenkins Family stated that the barn will be used in the same manner as the existing barn, including the storage and compost of manure at or near the barn. The Abutters have a reasonable fear that once the barn is constructed the odors will be stronger, the pests will be more prevalent, and the drifting smell of composting manure will affect their use and enjoyment of their property.

Odor and smell are legitimate zoning-related concerns that can be a basis for standing. See Rogel v. Collinson, 54 Mass. App. Ct. 304 , 315 (2002) (standing to appeal from denial of request for enforcement of zoning bylaw conferred where palpable harms caused by odors of urine and manure and dust produced by horses); see also Lydon v. Board of Appeals of Milton, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 1127 , 2011 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 849 (2011) (Rule 1:28 Decision) (finding that plaintiff had standing because mulch, loam, fertilizers, and other organic materials on the defendants property emanates odious and offensive smells onto plaintiffs parcel). The Abutters have presented sufficient evidence that they will suffer particularized injuries in the form of stronger noxious odors that will carry onto their properties if the barn is constructed. The Jenkins Family has not provided evidence to the contrary. The presumption has not been rebutted with respect to the Abutters claimed harm from odor.

2. Privacy

The Abutters also contend that they are harmed by decreased privacy. These harms, however, result from the clearing of the Locus to construct the barn, and not from the barn itself. Their articulation of this harm focuses entirely on the clearing of the previously wooded lot of the Locus and how the unobstructed lines of site did not exist prior to the clearing. See Wolff Aff. ¶¶ 12-24; Newell Aff. ¶¶ 12-19; Peña Aff. ¶¶ 25-30. The Abutters have presented no claim or evidence of any decrease in privacy as a direct result of the barn. The clearing of the Locus is not the subject of the action taken by the ZBA, and the Jenkins Familys ability to clear the Locus and use it as a pasture is permitted as a matter of right and cannot serve as the basis of a legally recognizable harm. The Jenkins Family has both rebutted Abutters presumption of standing on these grounds and demonstrated that they cannot form a basis for the Abutters standing.

3. Stormwater Runoff

The Abutters allege that they will be harmed by increased stormwater runoff from the Locus onto Canoe Tree Way West and the Newell Property, which will result in significant expenses to prevent further erosion or remedy the damage. To bolster their assertions, the Abutters submitted a Stormwater Impact Report (the GZA Report), which evaluated whether the addition of the barn will alter stormwater runoff volumes, patterns, and rates, and what impact that changes to the Locus will have on neighboring parcels. App. Exh. 17. The GZA Report examined stormwater flows for the Locus under three separate conditions: (1) pre-clearing condition, (2) post-clearing condition, and (3) proposed improvement condition (with the barn and gravel drive in place as proposed by the Jenkins Family). App. Exh. 17. After using rainfall data for Massachusetts storm events and modeling these events under the three different conditions, the GZA Report concluded that while stormwater runoff conditions indicate that the clearing of the lot resulted in increased stormwater runoff volumes and peak flows over the baseline wooded condition . . . there is no significant change in runoff volumes or rates between the post-cleared condition and the proposed condition (the addition of the barn and gravel drive). App. Exh. 17, Page 3.

The only other evidence Abutters present is from their own observations that they have noticed an increase in runoff from the Locus onto their properties since the lot was cleared. See Newell Aff. ¶¶ 20-22. As with the alleged privacy harm, the Abutters do not distinguish between harms from clearing the Locus and from building the barn that is the subject of the Decision. The Jenkins Family was entitled to clear the Locus as a matter of right, and any increased runoff from the clearing is not a harm resulting from the Decision. The Abutters have not presented any evidence relating to increased runoff as a result of the barn. Hence, the Jenkins Family has both rebutted Abutters presumption of standing on this ground and demonstrated that it cannot form a basis for the Abutters standing.

4. Traffic

Finally, the Abutters are concerned about the increase in traffic that will result from the keeping of horses on the Locus. Currently, the Jenkins Familys three horses are kept in a converted garage on the Jenkins Property where they also park the horse trailer they use to carry the horses to and from the Jenkins Property. Visitors to the Jenkins Property include veterinarians who come a few times a year, blacksmiths who shoe the horses six to nine times a year, and local farmers who provide feed to the horses. This activity continues year-round and is not seasonal. See Jenkins Interrog. ¶ 18-19. Once the barn is built and the horses are kept on the Locus, the current traffic to the Jenkins Property will be diverted to the Locus. Because the Locus is directly across the road from the Jenkins Property there is also likely to be increased pedestrian and vehicular traffic across Canoe Tree Way West to and from the barn.

Since the addition of the Jenkins Familys three horses to the neighborhood, there already has been a noticeable increase in the amount of large trucks and trailers traversing Canoe Tree Way West and Canoe Tree Way. See Peña Aff. ¶¶ 13-14. Both roads are unpaved, private dirt ways. In particular, Canoe Tree Way West-the primary access way to the Locus-is a very narrow road, approximately 10 to 15 feet wide. See Peña Aff. ¶¶ 10-12. Driving on these roads is already hazardous for the Abutters and will only intensify with trucks and trailers attempting to gain access to the Locus for the care and maintenance of the horses and the barn. Furthermore, the increased traffic could lead to the accelerated erosion of Canoe Tree Way and Canoe Tree Way, exacerbating an already hazardous driving path.

An abutters concerns of increased traffic and threats to pedestrian safety as a result of a development are legitimately within the scope of the zoning laws. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 722, citing Circle Lounge & Grille, Inc. v. Board of Appeals of Boston, 324 Mass. 427 , 427 (1949). Even slight increases in traffic after construction have been held sufficient to make the plaintiffs aggrieved, so long as the evidence is not speculative. Id. at 723. The record shows that the Abutters currently use both Canoe Tree Way and Canoe Tree Way West to access their properties. The Abutters have a legitimate concern that after the barn is completed traffic on these roadways will worsen. Even if the increase to traffic is minimal, the concerns of the Abutters are neither too speculative nor remote too deny them standing on such grounds.

Of the four injuries alleged by the Abutters, the Jenkins Family rebutted the presumption of standing regarding privacy and stormwater runoff, and the Abutters failed to carry their burden of proof once the presumption vanished. On the other hand, the Abutters retain the presumption of standing regarding odor and traffic. They have presented evidence, which the Jenkins Family has not rebutted, of separate and distinct harms that arise from the building of the barn and not just the clearing of the Locus. Since the Abutters have properly alleged harms and retained their presumption, they have standing to challenge the Decision. The Court turns to the substance of the Abutters challenge.

The Decision.

The cross motions for summary judgment turn on two key issues: (1) whether § 10.12 of the Bylaw applies to the Locus; and (2) whether the Locus is considered a Residential Lot of Record as defined in § 9.03 of the Bylaw. The Abutters assert that neither § 10.12 nor the exception in § 9.03 apply to the Locus and the Decision should be annulled. The Jenkins Family argues that § 10.12 is applicable to the proposed barn construction on the Locus, and, alternatively, the Residential Lot of Record exception in § 9.03 also provides relief. Each issue will be discussed in turn.

In an action brought pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17, challenging the issuance of a special permit, the court shall hear all evidence pertinent to the authority of the board . . . and determine the facts, and, upon the facts as so determined, annul such decision if found to exceed the authority of the board . . . or make such other decree as justice and equity may require. Id. This review is described as a peculiar combination of de novo and deferential analyses. Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381 (2009), quoting Pendergast v. Board of Appeals of Barnstable, 331 Mass. 555 , 558 (1954). The court is obligated to hear and find facts in the action de novo; that is, without giving weight to the facts found by the board, but rather assessing evidence presented by the parties. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Board of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 474 (2012); see

Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc., 454 Mass. at 381 (no evidentiary weight given to boards actual findings). Applying those facts, the court must give deference to the boards legal conclusions and interpretation of its own zoning ordinance, and determine whether it has applied the ordinance in an unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary manner. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, 461 Mass. at 474-475; Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc., 454 Mass. at 381-382; Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 487 (1999).

1. Section 10.12

Obtaining some kind of zoning relief from the ZBA was necessary for the Jenkins Family because the Locus did not meet the Bylaws 150-foot lot-depth requirement for property in an R- 1 district. After they applied for both a variance and a special permit, the ZBA granted the Jenkins Family a special permit pursuant to § 10.12 of the Bylaw for the construction of the barn on the Locus. Section 10.12 of the Bylaw provides for special permits for the extension or alteration of preexisting nonconforming uses or nonconforming structures. The Jenkins Family asserts that this provision also applies to extensions or alterations of nonconforming lots, and claims it is well established that the ZBA has the authority to grant special permits for such lots. To strengthen their argument the Jenkins Family points to two cases that they argue are applicable to the present facts: Bransford v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Edgartown, 444 Mass. 852 (2005), and Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Norwell, 450 Mass. 357 (2008).

Both cases fell under the scope of G.L. c. 40A, § 6, because they involved the reconstruction of lawful nonconforming single-family residences on lots that met all dimensional requirements in the towns zoning bylaws except minimum lot size. G.L. c. 40A, § 6, states in relevant part:

[e]xcept as hereinafter provided, a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to structures or uses lawfully in existence or lawfully begun, or to a building or special permit issued before the first publication of notice of the public hearing on such ordinance or by-law required by section five, but shall apply to any change or substantial extension of such use, to a building or special permit issued after the first notice of said public hearing, to any reconstruction, extension or structural change of such structure and to any alteration of a structure begun after the first notice of said public hearing to provide for its use for a substantially different purpose or for the same purpose in a substantially different manner or to a substantially greater extent except where alteration, reconstruction, extension or structural change to a single or two-family residential structure does not increase the nonconforming nature of said structure.

(Emphasis added).

In Bransford, the plaintiffs appealed a decision from the ZBA to determine whether the proposed reconstruction of their single-family dwelling would increase the nonconforming nature of the structure on the lot under G.L. c. 40A, § 6. Bransford, 444 Mass. at 853. A Land Court judge held, and three justices of the SJC concurred, that doubling the size of the structure on an undersized (nonconforming) lot [would] increase the nonconforming nature of the structure, requiring the plaintiffs to obtain a special permit. Id. Similarly, in Bjorklund, the plaintiffs appealed a decision by the ZBA denying their request for a finding that the proposed quintupling in size of an existing single-family residence was permitted under G.L. c. 40A, § 6. Bjorklund, 450 Mass. at 358. The SJC adopted the concurring opinion from Bransford and held that the proposed reconstruction of a new and larger house would increase the nonconforming nature of the structure and thus, under G.L. c. 40A, § 6, would require the issuance of a special permit. Id. at 362. This holding was further developed in Glidden v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Nantucket, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 403 (2010) (finding that a special permit to remove the existing garage and build a pool house at a different site was properly granted by the zoning board where the lot was nonconforming and the buildings on the lot were pre-existing nonconforming structures), and Gale v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 331 (2011) (affirming the zoning boards decision granting a special permit for reconstruction of pre- existing nonconforming structure). See also Deadrick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 85 Mass. App. Ct. 539 (2014); Palitz v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Tisbury, 470 Mass. 795 (2015).

While these decisions address similar issues, they are inapplicable to the facts of this case. The common thread in Bransford and Bjorklund is that they dealt with the reconstruction of lawfully existing nonconforming structures on undersized lots. In other words, the fact that the lot was undersized is what made the existing structures nonconforming. Here, there is not now and never was an existing structure on the Locus. Rather, the Jenkins Family is seeking to construct a new structure on an undersized lot that for decades has remained a vacant, wooded parcel with no structures other than a utility pole and a wire fence. Section 10.12 of the Bylaw clearly states that it is applicable to only preexisting lawful nonconforming uses and structures. It says nothing about nonconforming lots. As discussed, lot size is merely a way in which a structure can be nonconforming. There is no lawful preexisting nonconforming structure on the Locus to which §10.12 could apply.

Since there is no preexisting structure on the Locus, in order for this section to apply there must be a preexisting lawful nonconforming use on the Locus. The Locus is located within an R-1 zoning district, which permits agricultural use, including the keeping of horses, as of right. The use of the Locus for keeping horses prior to the Application was a conforming use. A conforming use need not and cannot be extended or altered as a nonconforming use under § 10.12.

In short, the Jenkins Familys reliance on Bransford and Bjorklund is misplaced. In this case, there was no nonconforming structure to be altered, which is the foundation of those decisions. The erection of the barn is not a reconstruction or extension of an existing nonconforming structure because no structure has ever existed on the Locus. Moreover, by its very nature a use as of right cannot be nonconforming and hence cannot be the subject of a special permit under § 10.12 of the Bylaw. Section 10.12 was not intended to provide zoning relief for new construction on a nonconforming vacant lot, but only for pre-existing nonconforming structures and uses. The ZBAs apparent interpretation of § 10.12 as applying to nonconforming lots is unreasonable and incorrect, and is not entitled to deference. The term lot is littered throughout the Bylaw. If the Town wanted § 10.12 apply to nonconforming lots they could have amended the Bylaw to reflect this. In this case, the ZBA picked a section of the Bylaw that does not apply to the Locus and erroneously and unreasonably relied on it to grant a special permit. Because § 10.12 is inapplicable, the Decision granting the special permit to the Jenkins Family must be annulled.

2. Section 9.03

Alternatively, the Jenkins Family asserts that the Locus is exempt from the 150-foot lot- depth requirement, which was adopted by the Town of Marshfield in 1972, by virtue of being a Residential Lot of Record under § 9.03 of the Bylaw. Section 9.03 states in relevant part:

Any lot lawfully laid out by deed duly recorded, or any other lot shown on a recorded plan endorsed by the Planning Board pursuant to Section 81P or 81U of M.G.L. c. 41, which complies at the time of such recording with the minimum area, frontage, width, and depth requirements, if any, of the zoning bylaws then in effect, may be built upon for residential use provided it has a minimum area of 5,000 square feet with frontage of at least 50 feet and is otherwise in accordance with the provisions of Section 6 of the Zoning Enabling Act.

(Emphasis added).

Section 9.03 provides grandfather protection for new residential construction on lots that at one time were buildable. It is undisputed that the Locus did conform to the Bylaw at the time it was created. The issue is whether the proposed use as a horse barn and pasture is included within the definition of residential use as that term is used in § 9.03. The plain meaning of residential use means use for a residence. In G.L. c. 40A, § 6, the term residential refers to single or two-family structures. Id. The keeping of horses does not fit within such a definition.

In response, the Jenkins Family reasons that the term residential use should not be narrowly construed to include only family homes as described in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, but instead argues that the term should be interpreted to include all the uses allowed in a residential district. They contend that because horses are permitted as a principal use in the R-1 district, the keeping of horses is on exactly the same standing in such a district as a family home.

This argument is not persuasive. Both a residential use and a non-residential use may be permitted within a residential district. That a nonresidential use is allowed in a residential district does not make it a residential use. While there is no dispute that under the Bylaw keeping horses is an allowed use in R-1 (Residential Rural) zoning districts, it does not follow that such use is a residential one. Section 9.03 does not apply to non-residential uses that just happen to be permitted in residential districts.

Furthermore, the interpretation that the Jenkins Family wishes to give residential use is at odds with similar grandfathering protections in other municipalities. Courts that have dealt with this issue have concluded that G.L. c. 40A, § 6, and corresponding local zoning ordinances were enacted to protect a once valid lot from being rendered unbuildable for residential purposes. Rourke v. Rothman, 448 Mass. 190 , 196-197 (2007), quoting Adamowicz v. Ipswich, 395 Mass. 757 , 763 (1985); Seltzer v. Board of Appeals of Orleans, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 521 , 521-22 (1987); Medina v. Eonas, 20 LCR 638 , 641 (2012). These types of ordinances were meant to encourage housing, not the keeping of horses or other agricultural uses. Accordingly, § 9.03 of the Bylaw does not apply to the proposed barn, and cannot provide justification for the granting of a special permit.

There is neither a lawful nonconforming structure nor a lawful nonconforming use on the Locus that would make it subject to § 10.12, and a horse barn does not make the Locus a Residential Lot of Record under § 9.03. There was no lawful basis under the Bylaw for granting the special permit. The Decision must be annulled.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Abutters Summary Judgment Motion is ALLOWED and the Jenkins Familys Cross Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. Judgment shall enter annulling the Decision.

SO ORDERED

NORWIN WOLFF, PATTI C. WOLFF, KELLY L. NEWELL, EDWARD J. NEWELL IV, JAMES REICH, ELLEN A. O'CONNOR, CARLOS G. PENA, and MAUREEN PENA, v. TOWN OF MARSHFIELD ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, MICHAEL P. HARRINGTON, JOSEPH E. KELLEHER, ARTHUR VERCOLLONE, PAUL YOUNKER, JONATHAN RUSSELL and KEVIN McMAHON as they are the members of the Town of Marshfield Zoning Board of Appeals, and MARY JENKINS, SALLY JENKINS, and LYLE JENKINS.

NORWIN WOLFF, PATTI C. WOLFF, KELLY L. NEWELL, EDWARD J. NEWELL IV, JAMES REICH, ELLEN A. O'CONNOR, CARLOS G. PENA, and MAUREEN PENA, v. TOWN OF MARSHFIELD ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, MICHAEL P. HARRINGTON, JOSEPH E. KELLEHER, ARTHUR VERCOLLONE, PAUL YOUNKER, JONATHAN RUSSELL and KEVIN McMAHON as they are the members of the Town of Marshfield Zoning Board of Appeals, and MARY JENKINS, SALLY JENKINS, and LYLE JENKINS.